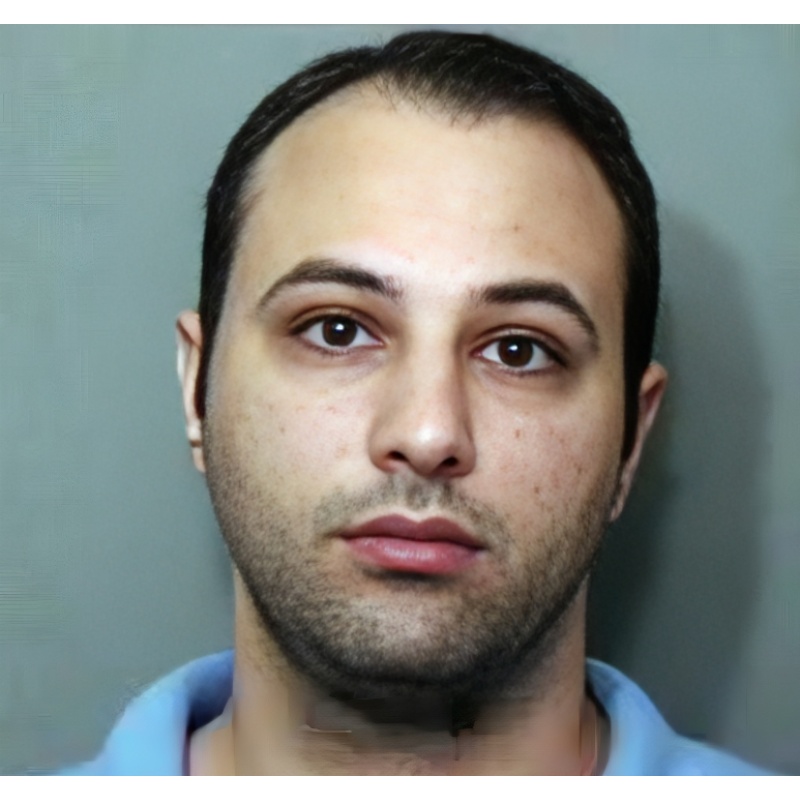

ADLEY H. ABDULWAHAB | $100 Million Fraud Scheme, Cheating More Than 800 Victims Across The United States and Canada | Serving 60-year sentence; scheduled for release in 2071 | Lot of 2 Autographed Documents Signed

LongfellowSerenade 27

Hedge fund manager and part owner of A&O Resources Management; convicted in 2011 of stealing $100 million from 800 victims by misrepresenting details about the company and concealing his prior criminal history; several co-conspirators were also sentenced to prison; the story was featured on the CNBC television program American Greed.

$20.00

- Postage

-

$0.00 to United States

Standard Shipping

Get Additional Rates

- Select Country

- Zip/Post Code

- Quantity

Description

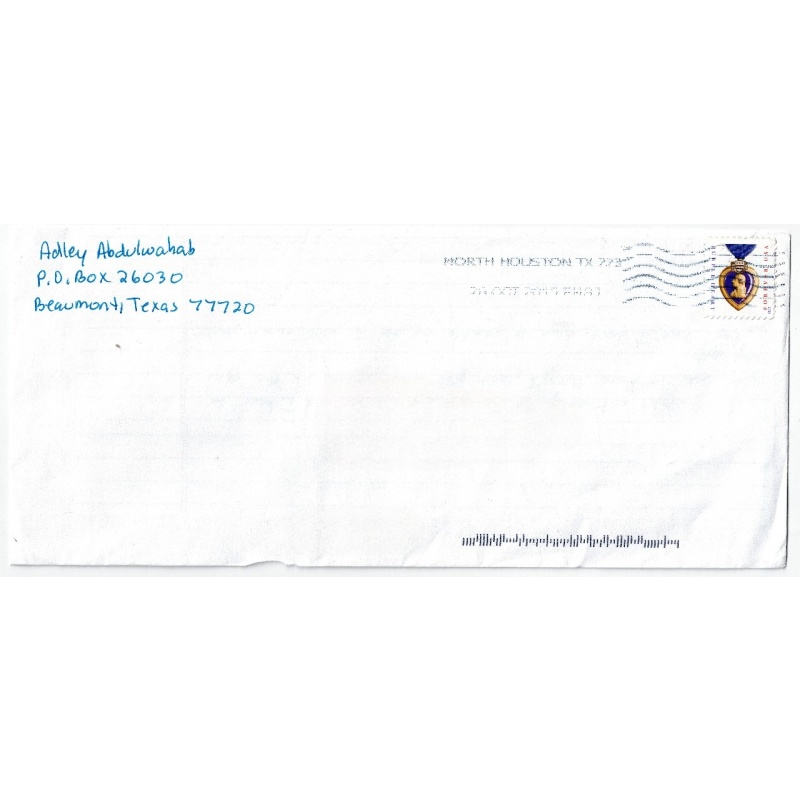

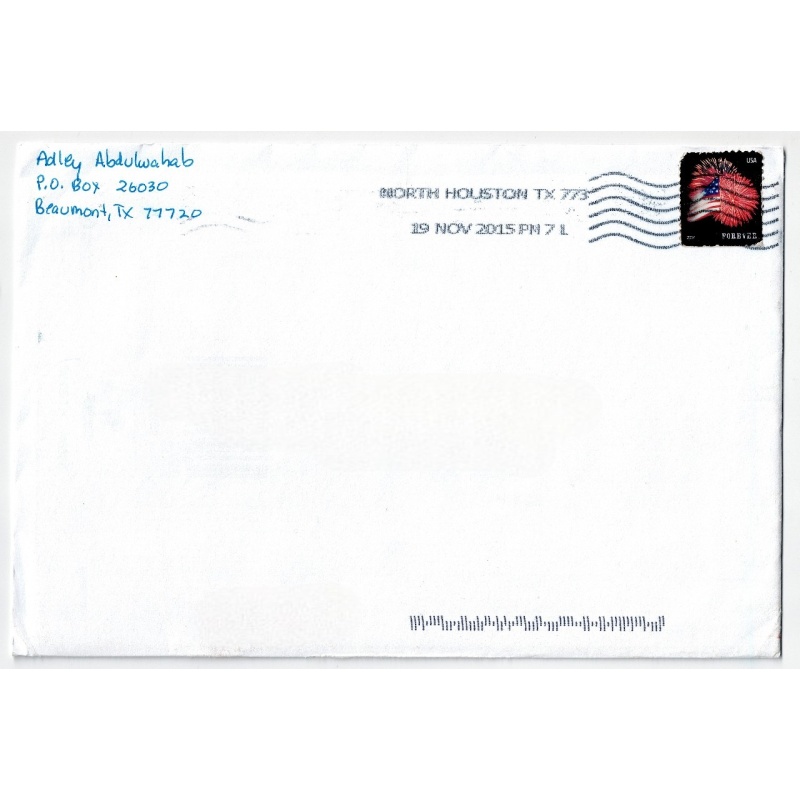

Adley Abdulwahab. Lot of 2 ADS: (1) Handwritten #10 Commercial (4.125” x 9.5”) Letter/Envelope. Pmk: October 26, 2015. SEALED. Content unknown. Pristine. (2) Handwritten #5 Booklet 5.5” x 8.125”) Card Envelope. Pmk. November 19, 2015. SEALED. Content unknown. Pristine.

“Mr. Abdulwahab participated in a $100 million fraud scheme, cheating more than 800 victims across the United States and Canada,” said Assistant Attorney General Breuer. “While lying to investors about his education and criminal history, he was off buying fancy cars with their money. Today, a jury let him know that financial crime has consequences, and that investment fraud will not be tolerated.”

On Sept. 7, 2010, a federal grand jury returned an 18-count indictment against Abdulwahab and two other principals of A&O Resource Management Ltd. and various related entities that acquired and marketed life settlements to investors. Today, Abdulwahab was convicted on all counts, including: one count of conspiracy to commit mail fraud, five counts of mail fraud, one count of conspiracy to commit money laundering, five counts of money laundering and three counts of securities fraud.

Christian M. Allmendinger and Brent Oncale founded a company known as “A & O” in Houston, Texas, in late 2004. The company sold life settlement investments, which are interests in life insurance policies. Until the end of 2006, A & O sold “bonded life settlements,” which were interests in particular life insurance policies. The investments were for fixed terms of between four and seven years. If the insured died during the term, the life insurance company would pay a benefit, but if the insured remained alive, a reinsurance bond, which A & O purchased from Provident Capital Indemnity (“PCI”), was designed to pay out and take over the life insurance policy (so long as the life insurance policy premiums were current).

Allmendinger and Oncale marketed and sold A & O's bonded life settlements directly to investors, and in early 2005, they hired Abdulwahab to market and sell their products. At the time, Abdulwahab was selling a different product for a different company, BHC Marketing. BHC soon terminated Abdulwahab, however, and he began working full-time as A & O's “national accounts director.” J.A. 116. Abdulwahab owned and operated Houston Investment Center (“HIC”), a Texas company that served as A & O's marketing arm. Through HIC, Abdulwahab employed mid-level sales managers who, in turn, supervised independent A & O sales agents around the country. A & O paid HIC its first commission on May 26, 2005.

In marketing A & O's products, both orally and through written materials they created, Allmendinger, Oncale, and Abdulwahab lied about many critical facts. For example, they represented that investor funds were placed in a segregated account dedicated to those payments and used right away to pay policy premiums up front. In reality, A & O had no separate account to pay premiums and A & O paid the premiums only as they became due. Indeed, A & O commingled investor money in a general operating account that A & O used for paying its bills.1 While A & O was operating, Allmendinger, Oncale, and Abdulwahab misappropriated millions of dollars from this account for their personal benefit.

The co-conspirators also misrepresented A & O's size, staff, and record of earning returns for its investors. In 2005 and 2006, A & O's websites listed fictional people as company principals, falsely stated that A & O had offices in multiple states, greatly exaggerated the number of A & O employees, and falsely stated that A & O had particular legal and business professionals on its staff. The sites also stated in July 2005 that A & O had “enabled [its] clients to leverage $375 million into $800 million in less than five years,” J.A. 120 (internal quotation marks omitted), when in actuality, no investor had received any pay out at that time and Abdulwahab had been informed of that fact. Abdulwahab assisted in creating the 2006 version of the website, and his business card listed the website address.

In 2006, Allmendinger and Oncale invited Abdulwahab, who was, at that point, responsible for 80–90% of A & O's sales, to become a partner. Thereafter, the three men each held an equal interest in A & O and shared authority over the company. Abdulwahab also was added as a signatory to A & O's bank accounts. HIC continued to market A & O's products, and A & O's commission payments to HIC remained unchanged.

By late 2006, regulators from different states began to send inquiries to A & O regarding its life settlement product, based largely on concerns that A & O was selling an unregistered security. These inquiries prompted the three partners to consult with Florida attorney Michael Lapat, who assisted A & O in setting up hedge funds that were backed by life settlements. By early 2007, A & O began offering fractionalized interests in these funds that they called “capital appreciation bonds.”

The three partners agreed that Abdulwahab would serve as fund manager. In the course of drafting the necessary offering documents and disclosures, Lapat used information from a document that Abdulwahab had completed earlier in 2006 in connection with an unrelated hedge fund (“the 2006 document”). Abdulwahab had falsely represented on that document that he had earned an economics degree from Louisiana State University when he had neither attended LSU nor obtained a college degree from any school. Abdulwahab had checked “no” in response to the question of whether he had “been convicted or pled guilty or nolo contendere, no contest ․ to a felony or misdemeanor involving investments or investment-related business, fraud, false statements or omissions, wrongful taking of property, bribery, forgery, counterfeiting or extortion.” J.A. 262 (internal quotation marks omitted). He also had checked “no” in response to the question of whether “[he] or an organization of which [he] exercised management or policy control [had] ever been charged with any felony or charged with a misdemeanor” of the type described in the previous question. J.A. 262 (internal quotation marks omitted). In actuality, Abdulwahab had pled guilty in 2004 in Harris County, Texas, to the felony of forgery of a commercial instrument. The court that accepted Abdulwahab's guilty plea deferred a final adjudication in his case and placed him on a five-year period of community supervision. Indeed, Abdulwahab was serving that term when he completed the 2006 document.2

Lapat used the 2006 document to draft a biography and the A & O funds' disclosure documents, including the private offering memorandum (“POM”). In so doing, Lapat discussed particular language with Abdulwahab. Because the POM was based on the 2006 document, the POM stated that Abdulwahab had earned his degree from LSU and did not disclose his felony plea. Although A & O regularly paid commissions of more than 10% to its sales agents, the POM nonetheless stated that A & O would invest 95% of investor funds in accordance with its investment objectives.

After making the change to selling capital appreciation bonds, A & O continued to operate in much the same way that it had previously, including using HIC to sell the bonds. A & O also continued to perpetuate various misrepresentations by creating new marketing materials. For example, the three principals and co-conspirator Eric Kunz drafted a “History Sheet” for A & O stating again that Abdulwahab had earned his economics degree from LSU, and A & O mailed this document daily in 2007 to sales agents and investors. In fact, A & O regularly utilized the mail to send marketing materials and investor documents.

As things turned out, A & O's decision to sell capital appreciation bonds instead of life settlements did not stem the tide of regulator inquiries. For this reason and because of some tension among the partners, Allmendinger, Oncale, and Abdulwahab agreed to sell A & O to a company called “Blue Dymond.” Before the sale, however, Allmendinger, Oncale, and Abdulwahab helped themselves—for what Allmendinger believed was one final time—to several hundred thousand dollars from A & O's operating fund. After this raid on A & O's coffers, only $2.9 million remained in A & O's bank accounts—not even half of the amount A & O needed to pay the premiums on all of its policies up through their bonding dates.

Abdulwahab was retained as a consultant for six months after the sale as part of the sales contract. However, although Allmendinger did not know it, Abdulwahab and Oncale had constructed an elaborate secret plan to purchase the company themselves and continue running it. Blue Dymond—the buyer of A & O—was little more than a front for Abdulwahab and Oncale; it was an offshore shell company created and funded by Abdulwahab and Oncale with the assistance of attorney Russell Mackert and without the knowledge of Allmendinger.

To fund the “sale,” Oncale and Allmendinger each deposited $380,000 from their personal A & O disbursements into Mackert's attorney trust account. Under the terms of the sale, the partners were to receive $750,000, with the expectation of an additional $250,000 in the 18 months following the sale. While Allmendinger received his $750,000 check, Oncale and Abdulwahab—unbeknownst to Allmendinger—each received checks in the amount of only $750 and secretly continued the business through Blue Dymond. Mackert wrote all three of these checks from his attorney trust account.

In September 2007, Mackert, at the direction of Abdulwahab and Oncale, also formed another offshore shell company, Physicians Trust, LLC, in the Caribbean Island of Nevis. This new company allegedly purchased Blue Dymond in order to further disguise Abdulwahab's and Oncale's involvement with A & O. That same month, Abdulwahab and Oncale hired David White to serve as A & O's president.

Through August 31, 2007, the date of the sale, Allmendinger had personally received $8,455,033.60 from A & O; Oncale had received $7,303,496.98; and Abdulwahab had received $2,889,366.70. With Allmendinger gone, A & O continued generally to operate in much the same manner as it had before. However, the remaining principals accelerated their misappropriation of investor funds. Indeed, after the sham sale, Abdulwahab and Oncale transferred approximately $10 million of investor funds from A & O's bank accounts to Mackert's attorney trust account, about $5.1 million of which was for Abdulwahab's benefit.

All told, A & O signed 843 investor contracts investing a total of $104,048,660.18 between 2004 and 2008. During that period, Abdulwahab personally received $8,002,904.78 from the scheme.

Mackert took over the management of the A & O entities in March 2008. A & O had stopped taking new investor funds by that time, and Mackert's role was essentially to make sure that premiums were paid, investor questions were answered, and investor files and policy files were protected. The policy premiums were to be paid in part from $4.6 million that White had paid to Prestige Escrow Company. In March 2009, however, Mackert discovered that Prestige had stolen a large portion of that money. In the next two months, Mackert undertook to determine how much money would be needed to continue to pay the policy premiums. He concluded not only that there was not enough money after the theft but also that, even had the theft not occurred, the $4.6 million “wasn't even close” to being sufficient to pay the policy premiums. J.A. 522. With A & O lacking sufficient funds to make premium payments, Mackert subsequently placed A & O into bankruptcy.i

VIDEO: 11-5093 United States v. Adley Abdulwahab 2013-01-29 | https://youtu.be/HzaMtMFw_3g

Archiving Protocol:

Handled with White Gloves ab initio

Photo Pages/Sheet Protectors: Heavyweight Clear Sheet Protectors, Acid Free & Archival Safe, 8.5” x 11”, Top Load

White Backing Board – Acid Free

Shipping/Packaging:

Rigid Mailer 9.5” x 12.5”. White, self seal, stay flat, kraft

cardboard, no bend. Each rigid mailer is made of heavy cardboard,

which has strong resistance to bending and tearing. Thicker that the

USPS mailers. Shipping cost never more than it absolutely has to be

to get it from me to you.

i FindLaw's United States Fourth Circuit case and opinions. (2023). Available at: https://caselaw.findlaw.com/court/us-4th-circuit/1629436.html (Accessed: 21 April 2023).

Payments & Returns

- Payment Methods

- PayPal, Money Order

Postage & Shipping

- Item Location

- 54911, Wisconsin, United States

- Ships To

- Worldwide

- Pick-ups

- No pick-ups

- Returns Accepted

- No

-500x500.jpg)